The Beautiful Game

The original plan forthe 2022 World Cup (Q22) called for nine new stadia in addition to three existing stadia. Since the approval of the plan in 2010, the building agenda has been scaled down to seven new stadia of varying capacities. A new metro system with a total length of 320 km will be completed in 2021. The entire effort will be a showcase for Qatari architectural design, engineering, urban planning, sustainability, transportation systems and fiscal management.

The design of the stadia will reflect aspects of Qatari and Islamic history and tradition such as a retractable roof in the shape of a tent, another reminiscent of traditional dhows used by Qatari fishermen as well as a design in the shape of traditional (male) Qatari headwear. There will also be geometric intricacies integrated into the designs echoing traditional art from across the Islamic world. Most of the new stadia will be repurposed after the Cup, turned into educational, sporting, healthcare and commercial uses with some components donated to sporting programs across the world.

All stadia will provide optimal conditions for players, match officials, spectators and media as they are equipped with retractable roofs and ultramodern (and in some cases solar-powered) refrigeration technology permitting year-round use. Each stadium will be a cocoon of comfort, preventing hot desert winds from penetrating while maintaining temperatures of 20-23ºC on the playing pitch while outside temperatures average 37ºC.

The dark side of accomplishing this massive task is that construction companies in Qatar hired manpower recruiters in numerous counties, Nepal among them, to dangle the benefits of working in Qatar. In a multi-year frenzy of semi-legal activity, these agencies charged recruits for costs, health checks, work permits, visas and airfare, in extreme cases totaling as much as $9000 each, an enormous sum for workers from one of the poorest countries on earth. The Qatari government was actively involved in this effort as well. A Nepali government investigation revealed direct (illegal) links between Qatari diplomats and the recruiting agencies. When the workers arrived in Qatar, they were already indebted to their employers who then paid only one-third of what they promised or in some cases withheld payment entirely for extended periods.

As of May 2017, over 400,000 Nepali migrant workers, half originating from a single indigenous group, had entered Qatar. They’ve had the lowest per capita income of anyone in Qatar. The $4B in remittances sent back to Nepal each year equal 20% of the entire Nepali national GDP, roughly equivalent to sixty minutes of economic activity in the USA. As the infrastructure build-out for Q22 is completed, further employment opportunities will dry up. This will have a significant impact on the Nepali economy, especially since Qatar and other Gulf states are seeking to diversify their labor base and raise the skill level beyond the primary sources of labor they’ve employed for the past decade.

Working 10-14 hours per day in extreme conditions without proper rest, sanitation facilities and living in sub-standard housing (often without wages), workers sustained an estimated 6500 deaths (from India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh) over a decade’s time, compared to a combined death toll of less than 30 construction labourers involved in the two previous World Cups. True, many of these deaths may not have been directly related to construction work. Nevertheless, that’s five workers from these countries dying every week since 2010 when Qatar was selected for the World Cup. Qatar barely investigated many of these deaths, classifying them as due to ‘natural causes.’

Even after the disastrous 2015 earthquake in Nepal, Qatar refused to allow workers to return to attend funerals or to care for their families. For years this modern-day slavery and indentured servitude went unchecked. In Qatar and the rest of the Gulf Cooperation Council states, until 2018, according to the kafala (sponsorship) system, all of this was essentially legal. Domestic help is treated the same way, and not only in Qatar.

Despite rising global criticism, as recently as 2019, a German broadcaster revealed video evidence that few of these practices had changed. Qatar started reimbursing recruitment fees to some workers in 2018 and enlisted over 200 contractors to comply. But determining the actual fees paid and to whom they were paid was a complication guaranteeing the number of workers reimbursed fell far short of the total deserving them. Some of the restrictions on worker movement were eased in 2020. Wages were increased 30% and employers were enjoined from retaining worker passports. Kafala was being dismantled. But as recently as March 2021, the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund declared they would be investigating questionable labour practices across Asia, including Qatar and those specifically related to Q22.

Meanwhile, in the boardrooms, university departments and government institutions, Qataris crow about staging a carbon-neutral world-class event. Carbon-neutrality, however, does not magically appear in a carbon-neutral way. The financing, sourcing and procurement of materials, however sustainably produced, is entirely dependent on revenues from extraction: the sale of offshore gas and the labour extracted to build the venues, the metro system, the parks, the new airport, the hotels and all the other amenities and accommodations of the event.

There are multiple initiatives such as ‘Green Hospitality,’ investments in appropriate carbon offsets and ‘sustainable operation practices’ to support the ultimate carbon-neutrality of the World Cup. But it all depends on visitors using the metro, recycling all waste and using recyclable plastic water bottles, marking a turning point in the standards of the local tourism industry. Qatar is leveraging the World Cup to push the hotels to elevate their game. Fair enough. In this respect, Qatar is indeed implementing progressive climate initiatives, but only at great cost to human and natural capital.

Qatar As Off-World

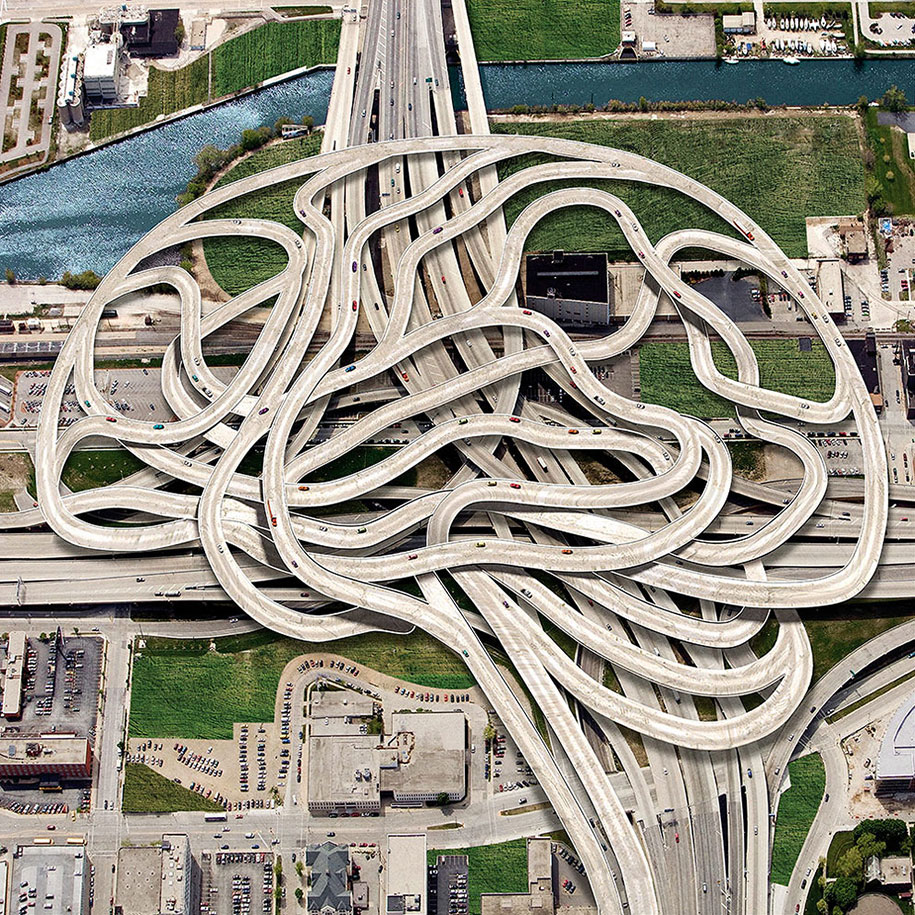

The extremes to which this nation must go to create or procure the basic requirements of life combined with the rising multiform risks associated with the Q22 effort are reminiscent of an off-world simulation, an artificial biosphere, the illusion of abundance surrounded by an unforgiving landscape, barely sustainable except by extreme measures. Surely there are few places where the interdependence between humans and the natural world is more clouded. Qatar defines the combined rituals of extraction and separation, the mechanics of it, the exploitive nature of it, the psycho-spiritual harm, the mass psychology of compartmentalization and denial to such an extreme that here, life itself is turned into a resource to be mined, leaving devastation in its wake. There is nothing new here. Instead of treating human capital as foundational to a successful society, it’s being used the same way as their offshore gas. Burned.

And here also is where the product of that denial emerges as multiple jaw-dropping architectural temples of sport, a gleaming futuristic skyline, steel and glass offerings to the gods of permanence, every comfort either accessible or constructed for the micro-managed spectacle of ‘earthly’ competition, sponsored by all the same ubiquitous multi-planetary corporate brands to be simulated and broadcast in endless detail back to the proletariat, attended by the international glitterati, entirely compatible with an artificial ethos of extreme resort living, creating new standards of excess, but without the inconvenience of interplanetary hyper-sleep. This is not some dystopian future. This is now.

Qatar and the other Gulf States are in a special class of nations driving the global legacy energy system, where the belief in their own illusions is reinforced at every turn while the reality of barely restrained plunder and its real-world consequences is cloaked in PR campaigns and market-speak. By the extremity of their lifestyle, they symbolize an apotheosis of Western nihilism, the radical divorce from ecological foundations and our headlong drive to collapse. There is only a contorted facsimile of belonging here.

One might argue that Qatar is doing everything right. They are conserving their natural assets, diversifying their $300B sovereign wealth fund to hedge against oil price fluctuations, investing in prime real estate in London and New York, shopping malls in Turkey, renewable energy projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, private and public companies throughout the world, venture capital and global tech. They’re catering to international tourists. They’re aggressively reducing methane leakage from their drilling platforms, redesigning their desalination plants, planning for their future and building their renewable portfolio. But at the same time, as their national carbon footprint falls, the risks are not disappearing: inundation by a rising sea, draining what little aquifer they still have, poisoning the life of the Gulf, human rights, the rights of nature, the living nature of earth.

Bismillah-ir-rahman-ir-rahim. In the name of Allah, The Most Gracious and Compassionate, The Most Merciful…

This sacred phrase, known throughout Islam, is repeated throughout the Qur’an. It is said to contain the essence of the entire Qur’an, even the essence of all religion. With the most receptive heart, utter devotion and with the purest of intentions, practicing Muslims speak these words on a daily basis. It’s not that Qatar is pursuing selfish gains or profit for its own sake. In a devout Islamic nation such as this, largely governed by Sharia Law, leaning into the Wahhabism of Saudi Arabia and the community of its brethren nations, that would contradict religious teachings.

I began by calling Qatar an extreme example. Yet who is to say any nation cannot pursue the benefits of its wealth, share them among its citizens and showcase their skills and generosity to the world? Therein is the advancing and crushingly poignant reality: Qatar, like virtually all nations, no matter how many times the words may be repeated with utmost sincerity, is not on a trajectory to lasting peace or beauty as the Qur’an might have us believe. It cannot reconcile its extractive practices with the costs. Qatar, like the rest of the world, to a greater or lesser degree, is stuck in the same cycle of addiction and shortsightedness. Even with all its so-called wealth, it cannot save itself. This is our ultimate poverty.