The bardo teachings of Tibetan Buddhism identify six post-death transitional states: birth, death, meditation, dreams, dharmata and becoming. Likewise, there are six realms of being (gods, jealous gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hell beings) through which, according to karma, we continuously cycle during life.

The intense experiences we have in life can be connected to one of the six realms, but surprisingly, they may also be connected to one of the six after-death states or bardos. Most accessible to us all in life, the experience of the six realms also contain bardo experiences. In other words, throughout life, we may become entranced or motivated by one of the dominant emotions of the six realms of being (anger/aggression, desire, ignorance, pride, envy or pleasure) and find ourselves encountering such circumstances which can only be considered bardos because of the imperative they present to us by their extreme nature.

The clearest way to describe this condition is to realize that each dominant emotional state of being contains the possibility of bardo experiences within it. We may cycle through realms by a lifetime or by the hour, but most likely we are in one or the other for limited periods except in the most extreme cases when we are truly stuck in a single realm to such an degree that there’s very limited possibility of ever escaping. The paranoia/envy of the jealous god realm (asuras) or the anger/aggression of the hell realm may well become prisons. But we may also be equally blinded by the pride of the human realm.

Each behavior type (realm) is like a station, a home base, a default field of awareness, our personal preoccupation with a way of comprehending our world. The experience of each station is not strictly limited to its intrinsic nature that one could never experience qualities or domains associated with other stations. Your station is determined by karma. Associated domains, the states we venture into away from our default domain, are more transient. So while we may spend most of our time in one or another realm, we can still have affinities with others. Within our dominant realm, we can—and will–have any type of bardo experience.

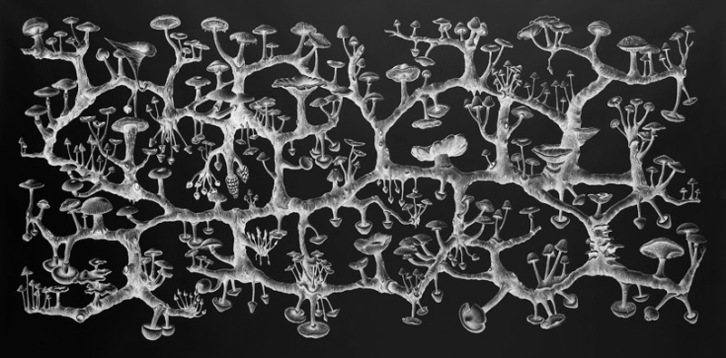

The translation of the word bardo refers to being ‘in-between islands.’ These ‘islands’ (call them states of mind or emotions that drive our lives) appear as obstacles, predominant mind-states such as fear or aggression, compassion, or perhaps gross events, life-long dynamics or ‘karmic’ predispositions. Islands become obstacles when we get attached to them, set up residence and interpret the world through their narrow lens.

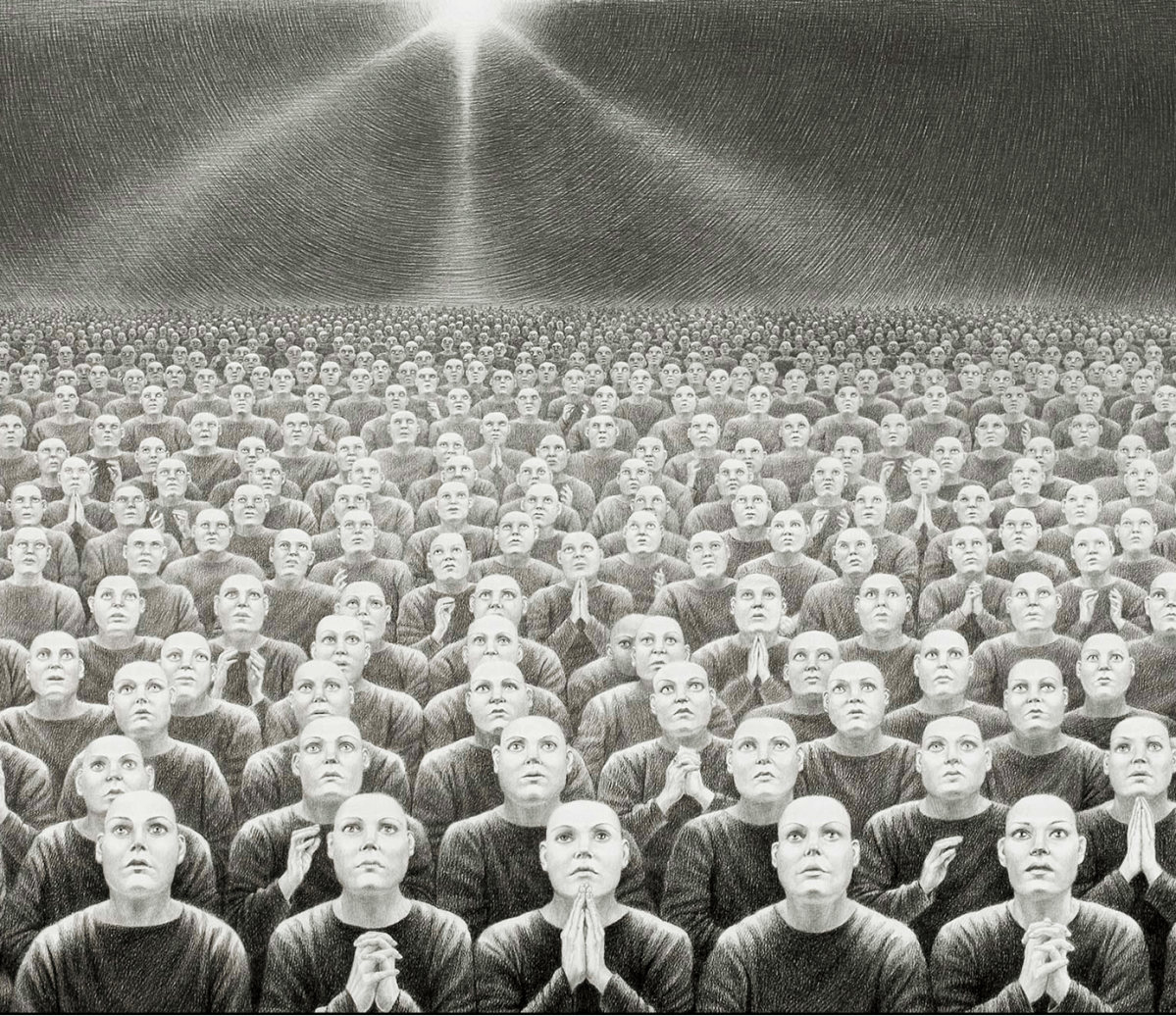

The steam or the river of consciousness is natural mind, a more awakened state. This is a state beyond bardos, existing in the gaps of experience. Since realization is regarded as an unchanging state of infinite space without origin or cessation, that awakened condition (of staying ‘in the stream’) implies an escape from all realms and all bardos. From that point of view, all identification with ego is an island we encounter in the stream. We are constantly running into and climbing about on these ‘islands,’ which are mere appearances in the flow of experience, sometimes for short periods and sometimes with a profoundly anchored grasping nature that makes it extremely difficult to escape…or ever return to the stream.

How we move through realms and bardo states implies we are perpetually jumping from one island to another and completely missing the stream because we are fundamentally misinterpreting our experience and perpetually grasping for antidotes to the flow of extreme emotional or psychic conditions.

If we take into consideration the Dzogchen view of a constantly refreshing arising and disappearance of phenomena, radical impermanence, then every arising of consensus reality is an island and every ‘gap’ between arisings is a ‘window of possibility,’ an opportunity to have an experience of true clarity, which would also be a bardo in that instant. The offer to awaken is always present. Entering that gap may be a momentary escape from a particular realm, but most likely, if karma has anything to say about it, any such ‘glimpse’ will stimulate an immediate descent into yet another antidote.

As markers of ego-identification, ‘islands’ are illusions. We can become entranced by the appearance of any island, such as personality, occupation, lifestyle, personal trauma, and cling to it, set up camp and live there-possibly our entire lives. We have experiences of pleasure and pain there, sometimes even misinterpreting what is pleasure and what is really pain. The way we relate to the islands is an indicator of the dominant realm we are operating in at the time, the way we are manifesting ego-based spiritual materialism. Being open to learning, such as in the human realm, distinguishes us from the animal realm, the jealous gods or the hell beings. But of course it’s all quite tricky. When pride and ego-driven indulgence and pursuit of peak experience and spiritual ‘attainment’ are the primary drivers, we, like religious fanatics, create our own brand of spiritual materialism and can easily imagine ourselves in the god realm. Another illusion.

Meanwhile, the river never stops flowing. Emptiness and impermanence are the only truths. The true nature of mind never changes, whether it is peeking through the gaps between every arising or in between our encounters with the ‘events’ of our lives, our karma or our perpetual wrestling match with ego.

Although the bardos are primarily described as after-death experiences, the meaning of bardo impacts everyday existence. It’s may seem complicated to understand existence this way, but this view opens a window of possible understanding that was not there previously. The bardo of existence (bardo of everyday life), dreams, the stages of physical dissolution immediately following death, the bardo of dharmata (non-duality) with its many visions, benign or fearful, the transition to the bardo of becoming presaging rebirth, all of it is described as the post-death appearance of islands in the stream and identified primarily with one or another of the six realms.

Going more deeply into the meaning of bardo and in relating the bardos to the six realms is a radically different way of presenting the entire proposition. We begin to understand bardos are falsely regarded as transitions between “permanent” conditions like birth, life, death and rebirth. But no, everything we regard as solid, any demarcation we may identify in life, its beginning, middle or end and all the consciousness along the way, are no more solid than any post-death bardo we care to name. It is always a function of ego to reify any or every aspect of existence. Simply by identifying everything as bardo, it all becomes transitional. Every moment is bardo, infused with the shifting attention of ego trying to make something to latch onto where there is nothing, controlling or clinging to or reacting to the appearance of every island with its various seductive opportunities for the comfort and safety of ego indulgence.

The Source

Out of nowhere, the mind comes forth

All is returned to you, beyond the cause

And effect: the oak tree

In the garden, chirp of crickets

Inside and out, aching knees

On a dusty mat. Without knowing it

We have wandered into a circle

Of wonder, where our confusion

Shines more

Outside the seeming errors and the search.

Wake up to your sleep

And sleep more wakefully!

—–Zachary Horvitz

From this view, the conception of the dream space of sleep is a metaphor of the waking space, a perpetual navigation of illusion in which, at least in sleep, the mind operates at subliminal levels, throwing images and stories before us and over which, if one seriously pursued dream yoga, one might eventually gain some control. The capacity to ‘awaken’ in the dream and even a capacity to write a new ‘story’ in the dream…or a new story of the dream is not only the story of dream yoga. It’s the reality of our waking condition.

The identity of the dream state, the waking meditative state, the post-meditative state and especially the immediate states upon physical death all present an identical opportunity: to cultivate a possible ‘awakening,’ a capacity to distinguish between illusion and reality, to recognize the activity of ‘mind’ for what it is and to meet every island appearing in the stream as an island without becoming transfixed. This is the context in which these interpretations of bardo imply–or verify, if you prefer– that every act, every moment in life, just as it is depicted in the after-death experience, is an opportunity to realize natural mind, a rehearsal for the post-death experience.

Those who are familiar with bardo teachings or practices or, for that matter, any meditative practice, may take a certain pride in accomplishment as we mark our progress. And we can attain a good deal of pleasure in the course of our practice. The pride of the human realm always sneaks in the side door whenever one believes one has arrived, when one imagines having achieved absorption or true equanimity, even for a moment. That is when one wishes to preserve it, to extend it, to own it or become it. But all of this is about hope and fear, and thus a form of spiritual materialism. In the extreme, this is the realm of the gods, who seek pleasures in every form, like notches on a belt. Sound familiar?

And at some point every edifice of attainment will dissolve into frustration and backsliding, becoming the opposite of pleasure and deconstruct into forms of ego-recrimination. All that attainment is impermanent! Damn! This is the bardo experience. This sort of confusion is identical to the character of post-death experience, perhaps the bardo of death, in which any hint of noticing the Nature of Mind, something that may already have arisen as part of our living practice, turns into such a striving that we instantly fall back into deeper confusion and even anger, the anger of the human realm or even something more toxic, the anger of a hell being.

So there we are, cycling and recycling in the whirlpool of samsara, confronting our own karma, particularly acute at moments of being so neurotically lost, so swept along in one or the other realm that we become deaf and dumb–we can’t hear or obey anything except ego. Lather, rinse, repeat.

I identify my existence along an axis between the human and the hungry ghost realms. There is certainly a desire to learn, an openness to what is new and even a willingness to let go of the trappings of my ‘personal monastery of achievement.’ I am largely free of the single-minded pursuits of the god realm, the paranoia of the asuras, or the fanaticism and anger of the hell realm, but at times I sense a descent into the hungry ghost realm in which I fail to relinquish anything and nothing is ever quite enough. There is a striving for more, more of something perceived to be absent.

This a form of aggression—an act of aggression upon the self. “I am not enough. I do not have enough. I am not good enough.” Blah, blah, blah. This hungry aggression is fundamentally materialistic, also a powerful and deep and pervasive character of humanity. The evolutionary path of humanity is to realize and confront this aggression and to allow it to die.

Aggression also operates in meditative practice. There are more different meditation practices than one may count. Many of them are beneficial in uncountable ways because they develop capacities which might otherwise never exist. But at the bottom of all practice, there must be a letting go of the striving, the need to manifest something, to fix something, to find something or even give up something. In life, you can be anything as long as you can also detach from being the one who believes in the need to be something. If there is an object of practice, it is to stop trying to be something, to unwrap the most subtle layers unmasking the operation and direction of the CEO, the games, identities, directives and assumed capacities of ego, until there is nothing left but living in the stream, free of all bardos. Non-meditation.