The basis of Jem Bendell’s original and revised paper on climate-induced societal collapse and Deep Adaptation was his review of current climate and public opinion research. In addressing the probability of societal collapse, his paper was and remains a contribution to popular understanding of the social implications of climate change, mainstream environmental advocacy and our current predicament. The definition of collapse he chose was an uneven ending of our normal modes of sustenance, shelter, security, pleasure, identity and meaning. Any distinction between collapse and catastrophe was not addressed. And, by the way, what is “societal” anyway? Whose society? Perhaps this omission was intentional, but clearly, he regarded any more specific definition of collapse as a separate pursuit.

Bendell was obviously content with allowing collapse to remain mostly a subjective frame, which would account for wide differences in definition depending on whom is talking—and where. What, after all, is the normal mode of sustenance or shelter, or even pleasure? And what is normal? If sustenance was overtaken by a revolution in food production that fed more people for less money and didn’t even require soil, would that be an ending of normal? Security is also an awfully big tent if it contains governance, rule of law, energy, health care and public health. Burning the last drop of oil would certainly be an ending, but would it be collapse? The fact that there was no serious effort to be more specific, even if it might have proven as difficult as picking up mercury with your hands, guarantees that readers remain within their subjectivity without much questioning and that the resulting variability of responses don’t represent a very reliable measure of anything. Perhaps it’s only what people believe that’s important.

Bendell also goes to great lengths to describe different psychological strategies, including denial within the environmental movement itself, for mitigating direct confrontation with advancing collapse and especially how we, particularly scientists, steer away from alarmism. Bendell has been criticized for making declarations potentially triggering despair. Different cohorts, whether scientists, laypersons, academics, different age generations or even samples from widely different cultures may have very different ideas about what collapse would look like. But in the absence of (even flawed) parameters, we are left to imagine the worst possible scenarios and a very hazy timeline in which they might unfold. Bendell may have had good reasons to avoid defining collapse any more specifically than he did, but his orientation, given the evidence he was citing, was solely to advancing climate impacts without much attention to political or economic dynamics.

In that avoidance we lose (or overlook) a capacity to evaluate whether collapse is already progressing according to dynamics not directly linked to climate impacts per se, or whether in grappling with a definition we might inevitably expand our understanding to include dynamics that only become more visible and valid according to a systemic perspective that doesn’t arbitrarily exclude those social, political and economic dynamics.

Collapse also deserves a closer (and wider) review because it carries implications for determining whether climate signs already exist, whether there are additional signs of collapse which may not be specifically climate-related but will augment climate impacts, and because the use of this term in this context appears to exist within a limited ethnocentric (global North) perspective. Whether collapse is already here for parts of the global south or whether it remains at a comfortable distance for the industrialized north is not even an open question. It’s difficult to tell whether Bendell was writing for a limited audience. But for the north, at least, we are already fascinated and appalled at the same time, hovering between hope and despair as events increasingly break through our dissociation. But for areas of the South, the signs are more advanced and already clear.

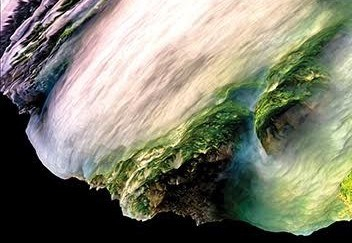

If we considered a single individual as a metaphor of global human systems, we could easily diagnose the patient in the grips of a profound ecological disease, even a pathology, gradually taking over. The fever is rising and the patient is in increasing distress. We see organ systems on the way to failure. From Bendell’s view, collapse represents a transition of the patient into an unmanageable condition, human systems failing to remain in any semblance of harmony with the biosphere. In other words, how can we speculate about when collapse may occur without naming the signs of illness, the social and environmental symptoms along with those strictly related to carbon emissions?

Just to be slightly more precise, although collapse may be perceived as a response to catastrophic events such as the permanent loss of polar ice, the jet stream or the Gulf Stream, it’s more likely to be a slowly unfolding emergency (uneven, as Bendell said) whose impacts aggregate over time. How long that time may be could vary from 10-50 years, or even longer. The question is, where is the inflection point between a normally functioning society and one that is coming apart—or will we only know in retrospect? There will be many signs, increasingly varied and disruptive. There will be mitigation, from mostly effective to increasingly futile. There may be rampant denial and spreading panic. How much deforestation does it take to upend normality? How much pollution? How much ocean acidification before the food chain collapses? Is fascism a sign of greater or lesser security? Is mass surveillance a sign? Is the pandemic a sign?

We are challenged to investigate relationships among an increasing variety of events and systemic adjustments to come to conclusions about what is climate related and what may not be, realizing that as time passes, the increasing number of events portending collapse will most likely be directly attributable to climate. And even if those relationships appear to be tenuous, the reality is that all events are data points illustrating the operation of a social, political and economic regime driving violent global change.

Bendell’s references to climate research include numerous big picture metrics such as sea ice, ocean acidification, the atmospheric carbon budget and changing weather patterns. He bases his theory of inevitable collapse on these advancing measures across numerous defined ‘tipping points’ and makes a case for near-term collapse based on these and additional effects of existing carbon emissions already baked into the atmosphere. The aggregate of emissions playing out over the next 1-3 decades will, he asserts, guarantee disastrous impacts. Likewise, despite the potential for sequestration practices at significantly greater scale or for radical reduction in emissions, the fact is we are adopting neither of these measures to the degree necessary, increasing the probability of collapse.

In addition to calculations of carbon emissions and sequestration, Bendell includes further and more recent data on the measurement of methane emissions and the likely scenario for their acceleration and resulting amplified climate effects as well. This is high-level analysis permitting the most general speculation about the sustainability of human and ecological systems and the likelihood of unpredictable effects on civilization, both agrarian and ocean-based food systems, human migration, disease and the loss of biodiversity.

The greatest proportion of global carbon emissions comes from a limited number of affluent nations. There is no dispute about this. We know the effects of those emissions will fall first upon less developed economies and peoples, but their impacts will also fall on local communities. In fact, while much of the affluence of industrialized nations derives directly from resources extracted from less-industrialized nations and guarantees the true costs of fossil fuel exploration and consumption to fall on those nations, the costs of other resource extraction practices also fall upon those less-developed economies.

In case one needs examples of these practices to fully grasp the nature of globalized exploitation and the externalization of ecological effects, we need only look at the tar-sands operations of Canada and Colombia, the destruction of the Niger Delta, toxic residues in Ecuador, the deforestation of Indonesia, the burning of the Amazon, mountaintop coal mining and the destruction of water resources in the US. In other words, the wealth and hence the carbon footprint of industrialized (white) nations derives primarily from the appetites and extractive practices of those nations in the global south.

In the most general terms, what collapse looks like is the transition of a society from greater to lesser complexity. Outside westernized urban centers, much of the global south is already less complex than the industrialized north, with agrarian culture’s economies more localized and resilient. But since Bendell shies away from defining collapse (or catastrophe) in anything other than the most general terms, one gets the impression the destruction he speaks of will only become real when it effects industrialized societies who have benefited the most from emitting carbon—at the expense of everyone else–and that their very development and stability insulates them from initial and less dire effects of climate disruption.

Indeed, Bendell rattles off the list of recent international institutional efforts created to mitigate the effects of climate by building resilience into developing economies. Unfortunately, these efforts aren’t much more than institutional green-washing, too little and too late. While the North refused in Paris (2015) to adequately compensate the South for climate impacts, giving themselves the freedom to define their own mitigation efforts in the absence of any enforcement mechanisms, they sloughed off their responsibilities to underfunded excuses, continuing Business As Usual and guaranteeing catastrophe far away from their own shores.

Meanwhile, contemplate just a few drivers of uneven endings:

- The massive and unprecedented shift of wealth upward for the past four decades

- Unregulated capital markets and the creation of phantom economies using unregulated speculative financial instruments, shifting risk to the collective.

- Increasing extraction from labor and destruction of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards.

- Intrusive and controlling policy serving narrow economic interests at the expense of health, education and the welfare of the commons.

- Mismanagement of land and degradation of food safety: food and soil quality declining with monoculture, pesticides, additives, GMOs & preservatives.

What collapse feels like is also not a matter to ignore. What may not be at the forefront of awareness is rising anxiety and apprehension about the security of current lifestyles, a viable future and the ability (not to mention willingness) of governments to respond. Do the incremental changes in perspective, the rising apprehension and pessimism about the future (solastalgia) count as a signal of collapse? The reality of these proliferating signs of economic and psychological stress are likely more widespread than we realize. And we’re not likely to be able to calculate their true effect until it’s too late.

Meanwhile, the North continues to generate climate impacts in the South, knowing the effects and continuing practices foretelling social disruption and eventual collapse elsewhere. Climate-related signs are already present, but again, it’s only from the perspective of highly developed western economies that Bendell presents the probability of collapse, failing to account for existing signs in less developed economies.

A few examples:

- Much of Bangladesh is under water. Between this year’s monsoon and a climate-amped cyclone, millions are affected by the pre-existing COVID lockdown, the closure of businesses, the loss of rural income usually provided by urban workers and the loss of arable land by erosion.

- Indigenous societies in Brazil are undergoing attack and destruction (ethnic cleansing?) by Bolsonaro’s aggressive agricultural development practices, directly driving climate change in the Amazon and the planet.

- Parts of the Pacific island nations of Fiji, Kiribati, Solomon Islands, Marshall Islands, Vanuatu and Micronesia are already disappearing. Human settlements, sanitation, agriculture and fresh water supplies are threatened due to rising sea levels.

- Disastrous multi-year drought and total crop failure in the north of Syria caused mass migration to the cities and, along with resource mis-management, foretold the destruction of that nation.

- Sudan is experiencing climate driven variability and timing of extreme temperatures and rainfall, disrupting food supplies, triggering civil war, the displacement of millions and a succession of either military dictatorships or civilian incompetence. Suffering is pandemic.

We could go on. It will likely be only when there are unavoidable signs occurring at home that developed nations will take notice:

- The rich central valley of California supplies a vast majority of all the fruits and vegetables for the entire US. Yet extended drought conditions have forced growers to tap groundwater supplies for years. Wells are now dropping 150 ft. or more into the falling aquifer. Water war is a long-standing condition between densely populated northern California urban centers and the agriculture industry. Factor in the declining snowmelt of the western Sierra and we have conditions eventually forcing choices between food and water.

- The Southwestern US relies on water supplies from the Colorado River and Lake Mead. Water levels of both have been in steady decline for decades. It’s only as matter of time before the viability of the metropolises of Phoenix, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are threatened.

- The UK wheat crop is the lowest in 40 years, foretelling a sharp effect on food prices.

Climate related migration has been already underway in many locations, causing economic and political destabilization. Coastal property insurance costs are rising and coastal land values are falling. Migration from the Florida Keys, Houston, New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta is rising. Whether it’s flooding or water scarcity in India, climate migration will result in unchecked urban growth just as it did in Syria, taxing inadequate infrastructure and further causing political and social stress.

What global events have been telling us for quite awhile and which have become especially clear very recently is that virtually no aspect of human presence, other than by reductionist efforts defining linear causation, can be culled from the whole and paraded before us as irrelevant to a calculation of impending collapse. Does collapse mean preventive measures have already failed? Would the implementation of security measures or the initiation of resource conflicts themselves represent collapse? Would mass food insecurity alone or rising crime in response to food insecurity constitute collapse? Does collapse imply a breakdown of governance, lawlessness or border disputes?

One of the most practical aphorisms of this age is to “think globally, act locally.” From this view the Deep Adaptation agenda makes sense, although it could stand some scrutiny and even radical expansion of what Reconciliation means from a global view. Personally, I see few signs of human resolve to revert to true reciprocity with the natural world in time to forestall broad collapse. Given the pace of events, the high degree of integration of global systems and realizing the entirely ethnocentric orientation of this agenda in the face of a huge disparity between the outlook and fortunes of the North and South, we might consider reversing the aphorism to “think locally, act globally,” asking what we need to do on an international scale to restore reciprocity and reverse the drastic inequities already playing out as consequences of our privileged over-consumption of carbon-based products. In doing so, we might even be saving ourselves.